Pierre Bourdieu et l’art de l’invention scientifique: enquêter au Centre de sociologie européenne (1959-1969)

Julien Duval, Johan Heilbron & Pernelle Issenhuth (eds)

Classiques Garnier, 2022

Pierre Bourdieu was eager to distance himself from the label that many publishers have nevertheless successfully applied: “theorist”. He would not assume such a tag, with its haughty philosophical baggage, without irony. His own preferred designation was “sociologist”, whose empirical scientific–and Durkheimian–connotations he exploited. Bourdieu seemed to revel in its modest status, noting as a kind of humblebrag that sociology is “devalued with respect to philosophy by its air of scientistic, even positivistic, vulgarity” and asserting the existence of a “structural discredit that sociology and everything associated with it suffers” (Sketch for a self-analysis, pp.15-16).

Though a bipolar opposition between esteemed philosophy and lowly sociology is not automatically comprehensible to us today, this new collection depicts the toil of the 1960s sociologist, showing all the ignoble, non-theoretical work on which Bourdieu’s repackaged “Theory” rests. To paint this picture, the book’s authors draw on several archival deposits, but most notably on Bourdieu’s own archives, contained in the Fonds Pierre Bourdieu, which was opened in early 2022. The authors focus less on Bourdieu as the conceptual architect that he would become and more on Bourdieu as the manager, administrator, data collector, liaison, correspondent,* and editor that he was during this period. The chapters orbit the work undertaken at the Centre de sociologie européenne, founded by Raymond Aron in 1959, with Bourdieu as its secretary from 1961. In sketching the Centre, the authors paint a vibrant research environment that flourished briefly due to a convergence of happy conditions and its component individuals’ self-sacrifice for the overriding project of the research group (p.121).

Such happy conditions must be understood in a relative sense, however. The authors describe constant financial shortages in the Centre, resolved through foundation patronage and short-term research contracts. Bourdieu is a core actor in the effort to secure these contracts while remaining cognizant of the importance of preserving research autonomy in the face of funders’ demands. Heilbron summarises Bourdieu’s goal as the attempt to identify “strategies [that permit] the preservation of the greatest possible freedom” (p.411). Among the agents from whom Bourdieu sought to preserve freedom while obtaining resources, the authors note the colonial metropole, Kodak (surprisingly tolerant of the sociological approach), the now-defunct Compagnie Bancaire, Editions de Minuit, and the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, among others. During this period, Bourdieu saw this kind of engagement as a necessity:

…the researcher must not shelter timidly behind the protection of scientific requirements to refrain from collaborating in applied research, which arises often unexpectedly and in a situation defined by urgency. [A note continues: “The caricatural attitude would consist effectively in agreeing to do only the studies that meet ideal standards of research in every respect, the surest way of never doing research”.] (p.306)

In conditions of material scarcity, the researchers channeled a “spirit of controlled improvisation” (p.415). This is evident in such moves as describing and recording interviewees’ home décor or posing as potential bank clients in something resembling an audit study avant la lettre (p.243). The very mention of such approaches gives reason enough for contributors to this collection to focus on the research practices, traces of which are preserved in the archives accessed. We encounter in this text the intermingling of research practices with tasks often derided as merely secondary or, at worst, as polluting pure research: correspondence necessary to secure an appropriate publisher, access to a punch-card sorter to process data,** and quotidian decisions concerning how to collect data in difficult circumstances (often answered by enlisting family members and students).

The editors make clear at the outset that the book’s chapters focus on these practices, for it is in the practices, rather than in any pre-existing set of theoretical premises, that the origins of what came later can be detected. As Heilbron puts it, “the book’s objective is to trace the genesis of a scientific oeuvre through analysis of the research practice of which it is the product” (p.13). This research practice is not to be understood as the practice of Bourdieu alone. Rather, arrayed around him and suspending him are members of a group. Along with practices, this group focus forms the second prong. In place of a fetishised, isolated theorist, then, we have a collective engaging in various research practices throughout the 1960s.

The first chapters detail Bourdieu’s approach to fieldwork and the development of his ethnographic techniques throughout Algeria (by Amín Pérez) and in Béarn (by Julien Duval and Pernelle Issenhuth). Inspired by the exhaustive ethnographic approach of Marcel Maget, whose writings Bourdieu describes as akin to a “microscope” on village life (p.78), the latter undertakes an almost indiscriminate collection of data. Enlisted in this practice of collection are some pivotal partners: in Algeria, Abdelmalek Sayad (Pérez has recently published a book on this relationship); and in France, his parents and his wife.

According to Pérez, Bourdieu finds in Sayad a figure analogous to himself: both come from rural backgrounds, attend relatively prestigious educational systems, and are anti-colonial in political orientation. Together, they sought to understand forms of violence that the anti-colonial war obscured and that existing journalistic forms of knowledge were not sensitive to. This endeavor, which aimed to escape orientalist abstraction, was nevertheless jeopardized by the war. The danger was real enough that student-researchers abandoned the group due to the risks. In such circumstances and with their naiveté, Bourdieu and Sayad opted for an expansive set of tools: from questionnaires and interviews to Rorschach tests and photography (p.51). Bourdieu intermittently returns to his home village in Béarn during this period, relating in writing to Sayad just how many parallels he–and Bourdieu’s father–observe between the lives and worldviews of the rural French and Algerians.

Bourdieu’s father was invaluable in the data collection process, as Duval and Issenhuth describe. This manifested itself not just by offering his connections to access informants and interviewees, but by participating, along with Bourdieu’s mother, in interviews (e.g., on photography in the peasant family). The authors reproduce Bourdieu’s written directions to his parents, which encourage them to suspend their customary habits of interaction during interviews and to remain vigilant in their observations (p.91). Marie-Claire (née Brizard), for her part, did tireless archival work in council halls on pre-Revolutionary Béarn legal proceedings. Much of this work appeared in Bourdieu’s work on unmarriagable men, but was geared towards a broader study of customary law. To aid in this, both Pierre and Marie-Claire uncovered, transcribed, and finally translated parchment records that predated the Napoleonic Code. Amidst this surfeit of data (Bourdieu complained at one point that he “knows too many things!” about this particular site [p.82]), there are hints of later developments: annotations convey observations about the dominance of (implicit) “ethos” over (explicit, Napoleonic) “ethics” and the increasing power of the legal specialist (the “scribe”), who begins the process of hoarding legal knowledge and produces a situation in which “there is an inequality before culture” (p.112).

The notion of culture was the cornerstone in the research conducted by those at the Centre de sociologie européenne. A number of central chapters concern this very topic (particularly those by Issenhuth on photography and education, but also one by Duval on museum attendance). The Centre was established after the founder of the VIth Section of the École pratique des hautes études, Fernand Braudel, sought American foundation money (Rockefeller and Ford especially). Aron provided impeccable anti-communist credentials and Rockefeller representatives esteemed him (p.133). So he was selected to found his own research centre, focused on Europe amidst a swell in Cold War-era “area studies”. After a slow start for his Centre, Aron elected Bourdieu as secretary (probably not Aron’s first choice, who was Pierre Hassner [p.137]), a position he retained until 1964 (when Chamboredon and Schnapper took over jointly). Bourdieu led an “équipe”, a research group within the Centre, something he acquired less at this point for his scientific aptitude than for his ability, demonstrated in Algeria, to lead research projects (p.148). Nevertheless, a kind of “Bourdieusian” research spirit or style does filter into the various projects the group carried out. This is evident in a few hallmark features: the reconciliation of sociology and ethnology; the identification of objects as “concrete totalities”, made up of relations; and an emphasis on scientific work as bound up with civic engagement (p.154). These features are familiar to those who have encountered the canonical Métier (or Craft) book that Bourdieu published in 1968 with Chamboredon and Passeron.

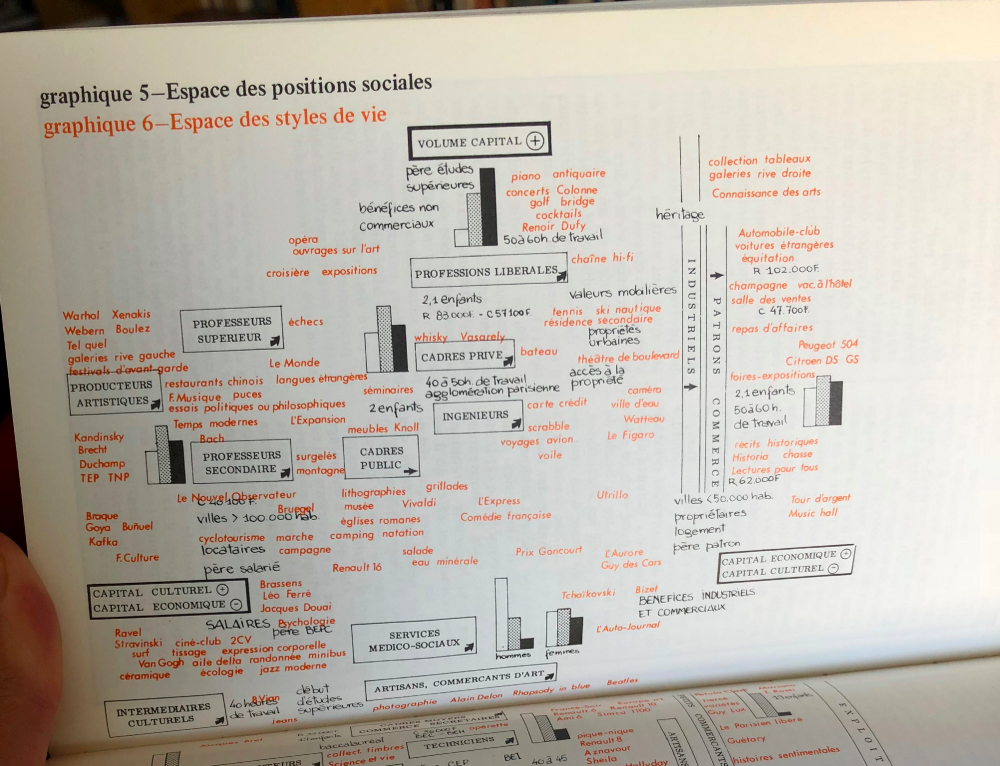

Issenhuth’s chapters on the studies concerning photography (whose products are published most notably in Un art moyen) and education (Les hériters and La reproduction) show the “cultural” interests of the Centre in the greatest detail. This is the case whether it is a matter of observing the back-and-forth between a contracting company (Kodak) and a research group, or following the unfolding of a research project (on education) as it increases in sample size and theoretical aspiration, with drafts and correspondence beginning to show signs of Bourdieu’s later intellectual framework. Despite the strict adherence of the authors of this book to a non-anachronistic account of this period (i.e., one that does not point out precursors to field, habitus, or capital at every turn), antecedents are difficult to avoid. For instance, Issenhuth describes a 1964 seminar in which Bourdieu and Passeron sketch the intertwined strands of class ethos, aesthetic values, scholastic ethos, and relation to the system of scholarly values as a composite set of variables responsible for explaining scholarly descisions and outcomes that contradicts “the myth of innate taste and the cult of the gift” (p.310). This foreshadowing of habitus is redoubled by an express intention, described here, to reconcile objective regularities with lived experience, something to be resolved through the notion of “taste”, which permits the spontaneity of experience without sacrificing determinism (in the form of social determinants of taste). This argument would be echoed and explicated fifteen years later in Distinction.

Though the person of Bourdieu is expressly absent in this book, it manifests itself at times, as in the sociologist’s anxious interest to impress Lazarsfeld with a large sample size and a mastery of statistical techniques (p.334).*** Like another recent work, Schultheis’ account of Bourdieu in the 1990s, this attempt to turn our focus away from the person inescapably reveals his unexpected facets. The reader departs having been disabused not only of their image of “Bourdieu the theorist”, but even perhaps of their image of “Bourdieu the empirical worker”, favored by many partial to him. The laborious research contained in these chapters (which, taken together, likely double as an excellent roadmap to the Fonds Pierre Bourdieu archives) brings to the fore an image of Bourdieu as administrator, entrepreneur, negotiator, and contractor (p.406). From this point of view, his esteem for intellectual autonomy comes less from the philosopher afraid of dirty hands and pollution by lowly tasks, and more from the worker sensitive to the precariousness of this privilege.

* Attention to the footnotes in this book is especially rewarding. The list of some of Bourdieu’s notable correspondents includes Emile Benveniste, Fernand Braudel, Raymond Boudon, Louis Dumont, Lucien Goldmann, Herbert Marcuse, Jean Piaget, Alain Touraine, and Paul Veyne, among other (overwhelmingly male) figures.

** This laborious process of disaggregating the sample by repeatedly–and often fruitlessly–feeding punch cards through the sorting machine, described by Salah Bouhedja and Francine Muel-Dreyfus in interviews quoted, is salutary reading for all those who take for granted an act of coding like filter().

*** Bourdieu would triumphantly recount meeting Lazarsfeld in the late 1960s, where the latter “literally ‘summoned’ Alain Darbel and me to the Hotel des Ambassadeurs…to tell us his criticisms of the mathematical model of gallery visiting that we had published in L’Amour de l’art. He arrived with a copy of the book on which he had scrawled in blue ink and, with a big cigar in his mouth, he pointed out, with some brutality, what he regarded as unforgivable errors. They were in fact in each case…crude misprints…. When these corrections were granted, Lazarsfeld declared with some solemnity that ‘nothing so good had ever been done in the United States’. But he took care never to put it in writing” (Sketch for a self-analysis, pp.74-75).